Dr. Ayla Göl*

ayg@aber.ac.uk

“The wheel of history turned at a blinding pace. … The people of Egypt have spoken, their voices have been heard, and Egypt will never be the same‟ [1]

Barack Obama

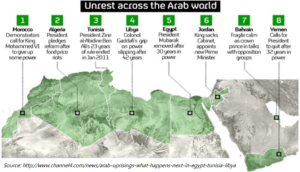

People are making an alternative history while revolution is sweeping across the Arab world. Since the fall of Hosni Mubarak on 11 February 2011, the unfolding pro-democracy protests and uprisings shook the Middle East and North Africa. The shock waves of Arab uprisings are rocking authoritarian regimes from Bahrain to Libya. Although Colonel Muammar Gaddafi is fierce, he is not the last champion of dictatorships that have been ruling Muslim countries for the last four decades. A street-level Arab revolt is taking place, which is unique in the history of the region. However, it is difficult to predict how these uprisings will evolve in the short, medium and long term. Each protest movement is distinct in origin in Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, Yemen and Libya yet they all share some common characteristics: the youth, unemployment of many participants, their internet savvy, and, more importantly, corrupt, rich authoritarian rulers who have been kept in power by the West. Furthermore, they have three unprecedented consequences and implications on how we see the Arab world and people: the importance of people power; the role of social media; and the evidence of the growth of assertive secularism in the Arab world.

Firstly, the voice in the Arab Street has been heard globally for the first time in history. Western news media describe this as the sound of people power in the Middle East and North Africa. According to social movement theory, these movements are usually organised, collective and sustained attempts operating outside conventional politics aimed at promoting social change. Historically, previous social movements have employed both violent and non-violent actions. Where they depend on methods of nonviolent action such as protest demonstrations, marches and political rallies they are classified as people power movements, which form a new political force to challenge the existing status quo peacefully. Since the late 1980s, people power movements have represented an alternative strategy for promoting socio-political change, grass-roots democracy, and redistribution of wealth equally in many parts of the developing world [2]. Not before time, they are emerging in the Middle East and North Africa of the 21st Century.

People power movements and revolutions do not occur without a cause. In the case of Egypt, mono-causal explanations obscure the complexity of these uprisings. There are a multiplicity of causes such as 30 years of one-man rule; Mubarak’s plans to pass presidency to his son; poverty; unequal distribution of wealth; unemployment; corruption; patronage; nepotism; a stagnant socio-economic and political system. Most importantly, when the Mubarak government refused to let international activists to enter the Gaza Strip during the Gaza Freed March on 31 December 2009 many Egyptians did not support this decision. Egyptian people felt that pro-Western Mubarak was betraying the Palestinian cause [3].

People power movements and revolutions do not occur without a cause. In the case of Egypt, mono-causal explanations obscure the complexity of these uprisings. There are a multiplicity of causes such as 30 years of one-man rule; Mubarak’s plans to pass presidency to his son; poverty; unequal distribution of wealth; unemployment; corruption; patronage; nepotism; a stagnant socio-economic and political system. Most importantly, when the Mubarak government refused to let international activists to enter the Gaza Strip during the Gaza Freed March on 31 December 2009 many Egyptians did not support this decision. Egyptian people felt that pro-Western Mubarak was betraying the Palestinian cause [3].

In addition to these political causes, there is straw that broke the camel’s back: In June 2010 a young computer programmer in northern Egypt was arrested and then killed. Despite the allegations by the Egyptian police that he suffocated as a result of his drug use, many eyewitnesses testified that Saeed was beaten to death by the policemen. When his mother and sister went to collect the coffin they were told not to open it. His mother courageously decided to defy this instruction and opened the coffin to find out the truth about her son’s death. Saeed’s sister took pictures of his distorted body and distributed them on Facebook. Within hours, his family and friends started a new campaign for ‘We are all Khaled Saeed’ on the social media that brought attention, not only to his suspicious death but crystallised the growing discontent about the undemocratic rule of the Mubarak regime that ultimately led to the ‘day of revolution’ on 25 January 2011 [4].

Meanwhile, in Tunisia, Saeed’s death was followed by the suicide protest of Muhammed Bouzani – a fruit-seller – who set himself alight because who could not find a job and he was despair at his poverty. In turn, his death in December 2010 set off violent protests that led to the so-called Jasmine Revolution in January 2011 [5].

Secondly, social media in the form of Facebook and Twitter have played a crucial role in spreading the news of Saeed’s and Bouzani’s death, making a wide range of mostly younger people aware of injustice and ill treatment of Egyptian and Tunisian governments and offering powerful tools for campaigning globally. However, the role of social media in Arab uprisings must be evaluated within a wider context of how technology, in general, and printing press, telegraph, radio, television and telephone, in particular, have all played decisive roles in the progress of history. The best example is the rise of print capitalism in the making of ‘imagined communities’, as argued by Benedict Anderson *6+. Social media itself cannot be effective unless it the message itself chimes with the wider public mood and unless it is used by people who are disseminating such messages. Once a society and people are ready for radical change and a movement emerges, various modes of communication are used to spread the new ideas. However, the role of social media should not be exaggerated given the fact that the use of internet and mobile phones can be blocked easily by authoritarian regimes. Moreover, although the social media were important, it was a book which acted as the bible of protesters in Egypt: From Dictatorship to democracy: A conceptual framework for Liberation by Gene Sharp [7].

Towards the end of his book, Sharp comes to three major conclusions: ‚Liberation from dictatorships is possible.

Very careful thought and strategic planning will be required to achieve it and Vigilance, hard work, and disciplined struggle often at great cost will be needed.‛ *8+

However, Sharp also cautions: ‚The often quoted phrase ‘Freedom is not free’ is true. No outside force is coming to give oppressed people the freedom they so much want. People will have to learn how to take that freedom themselves. Easy it cannot be.‛ *9+

It seems these ideas are exactly what young Egyptians acted on during the three weeks of protest that sent shockwaves around the Arab world. Their belief that liberation from dictatorship is possible was buoyed up by the successful revolution of their brothers and sisters in Tunisia.

Thirdly, in addition to the above-mentioned two characteristics rise of people power and the role of social media, these are secular uprisings. People from different religious (Muslim, Christian, Jew), ethnic and cultural backgrounds came together in Tunisia and Egypt. However, there have been distorted emphases on the threat of Islamist groups by Mubarak, Ben Ali, and Gaddafi.

The West has been too slow to recognise the simmering secular unrests in the Middle East and North Africa. Since the 9/11 events, the orientalist and essentialist discourses of the Western leaders and the western media have created the fear of the so-called ‘Islamic threat’. As a result, Islam and Muslims have become the focus of the politics of fear in the West. Historically, authoritarian rulers in the Muslim world have not hesitated to use the ‘Islamic’ card in order to oppress oppositions and to gain support from the West. For instance, Mubarak claimed that Islamists and particularly the Muslim Brotherhood, the Islamist group banned by his regime but still considered the largest opposition group, were behind the protests in Egypt. In fact, the Muslim Brotherhood did not support protesters initially. However, it was very quick to join the January 25 Revolution in order to have a voice in the transformation of Egypt [10].

Similarly, Ben Ali claimed that the Islamists were behind the uprisings in Tunisia. King Abdullah of Jordan stated ‘the dark hand of al-Qaeda’ behind uprisings. In Bahrain, the ruling elite claimed that Hezbollah’s bloody hand was behind the Shi’a uprisings. More recently in Libya, Muammar Gaddafi has joined the chorus by claiming that ‘al-Qaeda is responsible for the uprising against him’ [11]. It is nothing new. The authoritarian regimes and their leaders have always used the ‘Islamic’ card when they want to discredit any opposition to them emerging from the Arab world. Faced with choices between dictators and those tarred with the Al Qaeda brush, the West adopts the ‘better the devil you know’ position and thus helped to keep authoritarian leaders and dictators in power rather than dealing with Islamists.

By way of concluding, I would like to emphasise that the Arab uprisings are not only a profound challenge to their authoritarian regimes but also a wake-up call to the Western – and particularly American policymakers. The Arab uprisings show that people in the Middle East and North Africa want freedom, democracy, and human dignity like people anywhere else in the world. The Arab world is not the exception when it comes to democratisation. It is neither Islam as a religion, nor is it Arab culture that prevents democratisation. Rather, it is authoritarianism that is the real obstacle to democratisation. Western – and particularly American – policies towards the Arab world urgently need to be reviewed. So far, successive Washington governments have prioritised stability and thus their own easy to access to oil over democratisation. These policies are no longer sustainable. As the Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan stated with reference to Western interests in oil-rich Libya, people in the region ‚are fed up with being used as pawn in oil wars.‛ *12+ He also added that ‚the pride of peoples in the Middle East and Africa has been hurt enough by double-standard attitudes going on for decades,’ and he continued that ‚we call on the international community to approach Libya not with concerns about oil but with conscience, justice and universal human values‛. [13]

By way of concluding, I would like to emphasise that the Arab uprisings are not only a profound challenge to their authoritarian regimes but also a wake-up call to the Western – and particularly American policymakers. The Arab uprisings show that people in the Middle East and North Africa want freedom, democracy, and human dignity like people anywhere else in the world. The Arab world is not the exception when it comes to democratisation. It is neither Islam as a religion, nor is it Arab culture that prevents democratisation. Rather, it is authoritarianism that is the real obstacle to democratisation. Western – and particularly American – policies towards the Arab world urgently need to be reviewed. So far, successive Washington governments have prioritised stability and thus their own easy to access to oil over democratisation. These policies are no longer sustainable. As the Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan stated with reference to Western interests in oil-rich Libya, people in the region ‚are fed up with being used as pawn in oil wars.‛ *12+ He also added that ‚the pride of peoples in the Middle East and Africa has been hurt enough by double-standard attitudes going on for decades,’ and he continued that ‚we call on the international community to approach Libya not with concerns about oil but with conscience, justice and universal human values‛. [13]

Furthermore, even for those who would see the West primarily as a democratising influence, ‘democratisation by force’ is discredited since the US-led invasion of Iraq. The recent developments in the Arab world has crystallised another potential people power and revolution in world affairs. The politics of democratisation must be re-evaluated in the West in general and by the current American government in particular. This is a unique historical moment to restore the trust of regional people that Washington (and the West) is genuinely interested in ‘democratising’ the Arab world. If the West wants to have real democracies in the Muslim world they have to stop supporting authoritarian regimes. The rest will be decided by history and the people themselves. As Sharp highlights:

‚If people can grasp what is required for their own liberation, they can chart courses of action which, through much travail, can eventually bring them their freedom. Then, with diligence they can construct a new democratic order and prepare for its defence. Freedom won by struggle of this type can be durable. It can be maintained by a tenacious people committed to its preservation and enrichment.‛ *14+

For now, people in the Middle East and North Afri- ca face the challenge of constructing ‘a new democratic order’. Meanwhile, it is clear that authoritarian leaders and dictators in the Arab world are on the losing side of the history. Now, the West has to show whose side they are on. PR

Notes:

* Director, Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Contemporary Political Violence (CSRV); Lecturer in International Politics of the Middle East and Islamic Studies; Department of International Politics; Aberystwyth University. Email: ayg@aber.ac.uk

1) http://www.rawstory.com/rs/2011/02/11/obama- the-people-egypt-spoken/#

2) K. Shock, ‘People Power and Alternative Politics’, Politics in the Developing World, 3rd edition.

3) h t t p : / / occupiedpalestine.wordpress.com/2011/01/12/ei- deadly-gaza-bombings-as-orgs-decry-collective- punishment/

4) h t t p : / / e n . w i k i p e d i a . o r g / w i k i / File:Khaled_Mohamed_Saeed_holding_up_a_tiny,_ flailing,_stone-faced_Hosni_Mubarak.png

5) http://www. bbc. co. uk/ news/ world – africa- 12120228

6) Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London: Verso, 1991.

7) Gene Sharp, From Dictatorship to Democracy: A Conceptual Framework for Liberation, Boston: The Albert Einstein Institution, 4th ed., 2010. Gene Sharp: The US Scholar who inspires Middle East Uprisings, BBC News, 20 February 2011. See http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-12518436

8) Sharp, pp.77

9) Sharp, p. 78

10) Roula Khalaf, ‘Young Muslim Brothers push for transformation, Financial Times, 13 February 2011.

11) h t t p : / / e n g l i s h . a l j a z e e r a . n e t / n e w s / africa/2011/02/20112254231296453.html#

12) h t t p : / / e n g l i s h . a l j a z e e r a . n e t / n e w s / europe/2011/02/20112261532418665.html

13) http://www.hurriyetdailynews. com/n.php? n= turkeys- pm- speaks- out- against- l ibya- sanctions-2011-02-26

14) Sharp, p. 78